Teaching your children the difference between wants and needs

Explaining the distinction between what is desirable and what is necessary can be a challenge, but research shows that it is one of the most important lessons you can teach your children. So how should you go about it?

Most parents will be all too familiar with the experience: your child asks for a new toy, staring at you doe-eyed and stating earnestly that they “need it”. Understanding spending priorities can be challenging for many adults – after all, often one person’s essential is another’s luxury – so it’s little wonder that it takes time for young children to grasp the concept that something they want is different to something they need. Offer them the choice between buying a new games console or paying the electricity bill? The chances are they’ll opt for the console, not realising their enjoyment won’t last long when the power cuts out.

When it comes to your child’s financial education, understanding topics like these are paramount: a 2023 report by OneFamily1 found that only 47% of UK students have received meaningful financial education at home or at school, and that those who haven’t are less likely to save and feel confident about money. Recent research by Just Finance Foundation2 shows that people who do discuss money topics help children form good lifetime financial habits and make better and less financially risky decisions themselves. It’s never too soon to start teaching your children about money, so how can you start to introduce the concept of spending priorities with your youngsters?

Understanding where your child is coming from

Children are born with basic needs: food, shelter and security. But as they grow they are exposed to different influences which help them develop their own ideas and desires. From seeing which toys their friends have, to watching adverts on TV, plus more modern forces such as YouTube and TikTok influencers and targeted online ads, there are hundreds of ways in which children are swayed and taught to want. The essentials they need, such as a roof over their heads, clothes to wear and food to eat, have hopefully always been readily supplied by their parents, so teaching them that these things do not come for free, and also have a value and a cost, is an important component in addressing this issue.

“It’s essential that we have these conversations with children,” says Russell Winnard, Director of Programmes and Services at Young Money. “It’s only through explaining how daily life works that they can begin to understand how the world operates, and that many of the things we need, like electricity and heating, also have costs. Likewise, they may understand that a TV is a luxury and that it costs money, but they won’t factor in more discreet costs such as a TV licence. It’s important for children to learn what the essentials are, and then you can explain that ‘wants’ are the luxury items you may choose to buy if you have money left over. It all comes back to understanding the principle that ‘needs’ are the things we require to live and ‘wants’ are the things that enhance our lives if we have the money for them.”

The psychologist’s insight

According to leading child psychologist Dr Elizabeth Kilbey, it’s important to consider your child’s developmental stage when it comes to introducing this topic. “For younger children aged between five and seven, everything is a want. They live in a constant state of wanting everything, so they need your guidance. It’s key that parents model buying things, showing them the mechanics of purchasing and encouraging them to write a list of priorities for their wants.”

When it comes to older children aged between eight and 12, Dr Kilbey says you can start to explore the topic more fully. “At this stage there is an understanding of the difference between wants and needs, so although it might feel counter-intuitive, one of the best things for parents to do is allow their children to make mistakes financially – let them buy things with their pocket or birthday money that they thought they wanted, only to discover it’s actually nowhere near as fun as they thought. They need to realise that they could have saved up their money for a higher-value item that might have been better. It’s important for them to make these mistakes early, in the safety of parental control, rather than at 18.”

Whatever their age, Dr Kilbey says one thing is paramount: “The key concept we need children to understand is that money is a finite resource – only then can they weigh up decisions about it. Young children often have this notion that money is magical and never-ending. That’s why it’s so important for parents to say no sometimes.”

Introducing earning and priorities

Another way to help illustrate this topic is by introducing the idea of earning. “It’s never too early to talk to your children about where money comes from and how we earn it,” says Russell. “With slightly older children, I often ask them to look up the national minimum wage so they have some concept of the ‘cost’ of an hour of time. Once they do that it puts other things in context: they begin to see how many hours their parents might have to work to buy that games console or those trainers. It can be quite enlightening.”

Mohommad Chauhan, a MoneySense Volunteer and Community Banker from the Midlands, agrees that helping put costs in context makes a huge difference to a youngster’s understanding of wants and needs. “Recently I led a MoneySense workshop in a local school which asked pupils to work in groups to plan and budget for a reasonably-priced birthday party,” he says. “After they finished the exercise, I asked the class what they had learned, and one pupil said that the next time his parents were planning a party for him he was going to sit down and help them budget to see if there were places where he could cut costs. I was amazed by his attitude – he had really grasped the concept, which is particularly impressive at a time when kids are bombarded with social media influencers and adverts trying to sell them products that will purportedly transform their lives.”

To tackle this, Mohommad says the simple approach is often best. “I always start by asking children what they think the difference is between a want and a need, and then breaking it down with them. It’s really interesting to see them begin to understand: they might ‘need’ a mobile phone when they start secondary school, but they ‘want’ the latest model. That’s where earning their own money comes in – when they’ve worked hard to earn it, suddenly every penny starts to count.”

“Children often have this notion that money is magical and never-ending. That’s why it’s important for parents to say no sometimes”

Tackling pester power

Even when you’ve done your best to explain the differences between wants and needs to your children, there will be times when their desire for that new toy or treat morphs into every parent’s worst nightmare: pester power. Almost impossible to ignore a hundred percent of the time, pester power can prove costly to parents and prevent children from learning the value of money and how to prioritise needs over wants. The good news is that you can turn pestering into useful money learning opportunities.

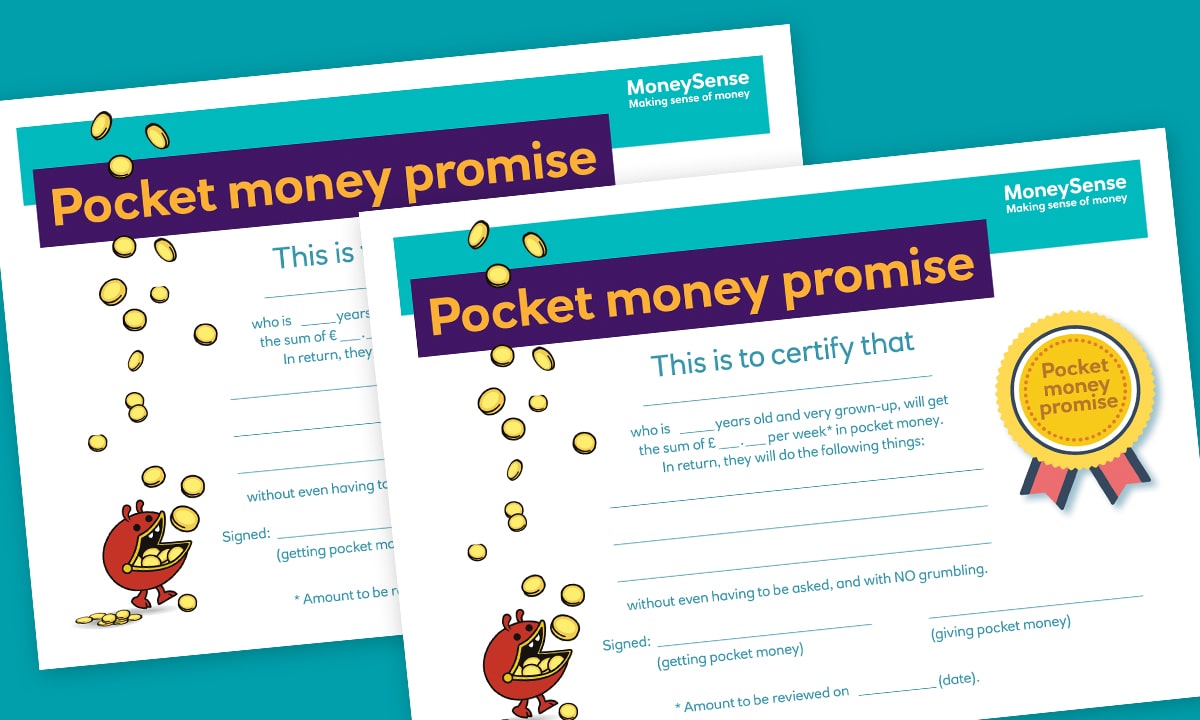

While it’s always going to be a challenge, Russell says that tackling pester power “comes back to instilling an understanding of the value of money, and of costs relative to earnings. In time, your child should begin to understand what they’re asking for in the context of the household income, but this is also why earning money, or giving your child pocket money if you can afford it, can help. Having ownership of their own money means they can start to make their own decisions. It’s a good strategy for adult life, too, since we rarely have all the money we need for everything we want to do.”

Practical exercises to try with your children

Challenge your kids to a game. Name something out loud or write a list of things (for example: water, toys, clothes, ice cream, holidays, a bed, day trips) and ask your child to identify whether it is a ‘want’ or a ‘need’. Discuss their answers and explore the thinking behind them.

Compare the costs of a take-away pizza to a homemade or shop-bought option. They might want what they see in an expensive TV advert, but is it worth the additional cost? Is there something else that money could go towards that your family needs?

Rather than giving into individual requests, encourage your child to write a list of things they want for their birthday or Christmas. Nearer the time they might realise they don’t want the same things they desired a few months ago. They can also prioritise which things they want the most, and if there are things on there they genuinely need.

Ask your child to calculate the cost of a family visit to the cinema, including transport, tickets and snacks. Now calculate the cost of a home movie night with shop-bought treats. What is the difference? Is it good value for money? What could the money you save go towards instead?

Sources:

1 Money and Pensions Service: Less than half of UK children have been taught about money (June 2023)

2 Just Finance Foundation: What Do Kids Know About Money? (August 2023)

3 Marketing Magazine: From the bottom up – the new pester power for good (Sep 2019) (Nov 2018)

Image credits: iStock

Additional MoneySense resources

Activities:

Activities:

Articles:

Articles:

Poster:

Poster: