Dealing with pester power

Wondering how to resist your kid’s repetitive pleas? Money writer and mother Clare Seal shares her tips.

Parents of young kids have all been there: you’ve said no once, twice maybe three times, and now they’re starting to wear you down. The capacity of little ones to repeat themselves knows almost no bounds – so how can you learn to remain firm? And why is it important that you do – not just for your own bank balance, but also for your children’s financial future?

What is pester power?

Pester power, aka ‘the nag factor’, is a technique employed by kids the world over to persuade their parents to buy something. Often, it’s a toy that’s been marketed to them, and this nagging campaign can prove both expensive and counter-productive if not dealt with effectively. Caving in to pester power can cause parents to end up spending more than they intend to, and sometimes even more than they can afford – but it can also be damaging to a child’s future relationship with money. Primary-aged children are just forming their ideas and attitudes towards money and, at this early stage, the way that you talk to them about money, affordability and getting what they want is important.

Why does pester power work so well?

Advertising products directly to children, who usually have no means to buy things for themselves, might not sound like the smartest move, but marketers have known for a long time just how effective using children to advertise by proxy can be. Instead of bombarding parents with messaging about how much their child will love a certain toy or game, they show it to the child, and allow them to do the hard work.

Because most parents have a higher tolerance for repetition from their children than from advertisers, pester power can prove far more effective than increased direct exposure to a product. Different people respond differently to this excessive hinting from their children but, by and large, parents want to please their kids and are often susceptible to having their heartstrings tugged, which can result in them caving in to the pressure. Not only does this make parents feel ground down, but it also teaches children that it’s ok to nag people for things – and that it might actually be an effective way to get what they want.

Why do children do it?

It’s easy to see the appeal of pester power for advertisers – but why do children find it hard to take no for an answer in the first place? “Pester power is a behaviour, like any other,” says psychologist Dr Elizabeth Kilbey. “Children can find it hard to delay gratification, so if they want something, they will make a concerted effort to persuade parents to get it for them. But the reason they keep on requesting something they want is because experience has taught them that if they keep asking, eventually they’ll get it. Children do it because it’s worked in the past.”

This makes it all the more important to nip this behaviour in the bud by responding in the correct way.

How can we respond in a positive way?

When it comes to pester power, Dr Kilbey recommends making your mind up about requests from your children quickly and decisively, and then standing by your decision – whether it’s yes or no. If you’ve said no in the first instance, stick to your guns and don’t respond to pestering, other than to calmly reassert your position. “Caving in to a request will increase the likelihood of children using pester power again. So, in this way, resisting is definitely the best strategy,” she says. “However, there are times when it might be a good idea to ‘cave’ – but you should be doing so because you’ve chosen to, not because you’ve been ground down.”

Helping your children learn that pestering isn’t the answer isn’t about saying no to every request. It’s about making sure that your decisions are final and that you’re not confusing your children by saying no at first, then agreeing later down the line because you’ve been pestered.

How do we talk to our children about it?

Dr Kilbey suggests keeping things short and sweet. “It’s important to explain that you’ve made a decision about their request and you’re not going to change your mind,” she says. “Once you’re sure they’ve understood, then it’s best not to discuss it any further as that just adds further attention to the scenario. You can distract or divert their attention by moving the conversation on to something else.”

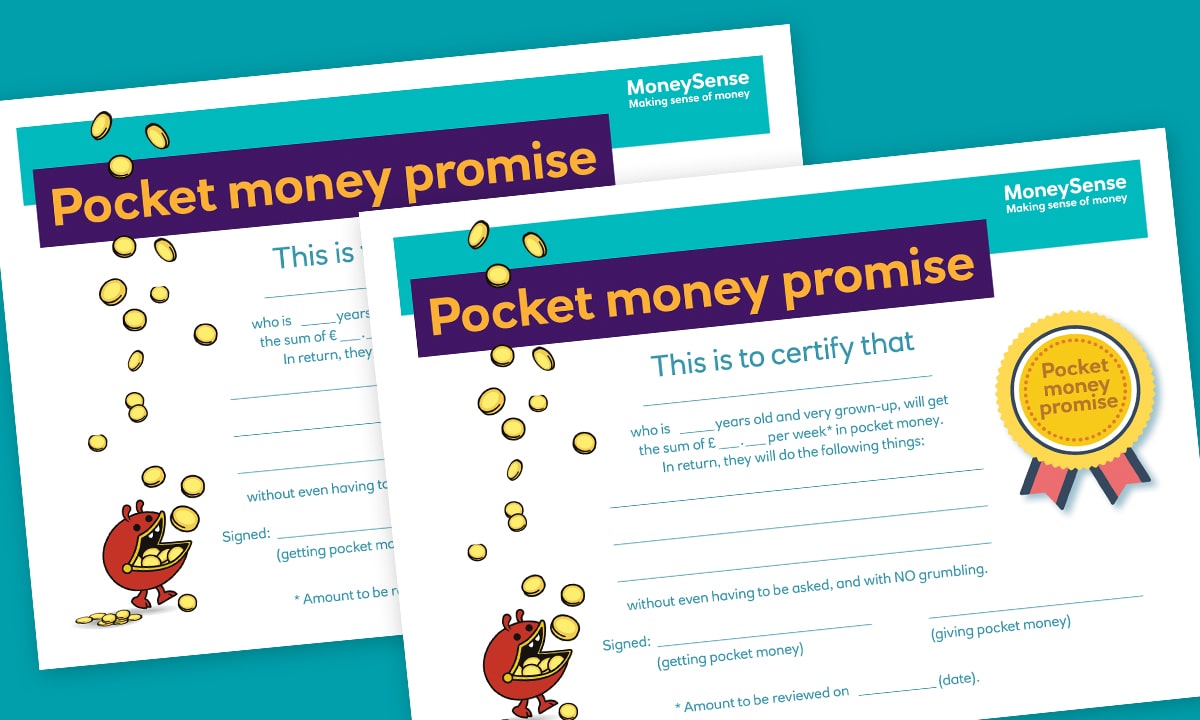

If your children are a little bit older, it might also help to share how their nagging makes you feel and to explain why it’s not the best way to get what they want. Giving older children a bit of context and the opportunity to see things from your perspective can be effective in curbing unwanted behaviour. You could also use items that might previously have been the subject of pestering to teach them about other useful skills such as saving and earning. You could make the desired item subject to a saving plan, where your child can earn extra pocket money by helping with chores, for example – this will help them to learn about their own role in getting things that they want.

Resisting pester power when you’re tired or busy can feel harder than just giving in, but by tackling the issue consistently, you’ll not only save yourself money and time, but also teach your kids an important money lesson.

Image credits: Adobe Stock

Find out about all the latest MoneySense articles for parents by following us on Facebook

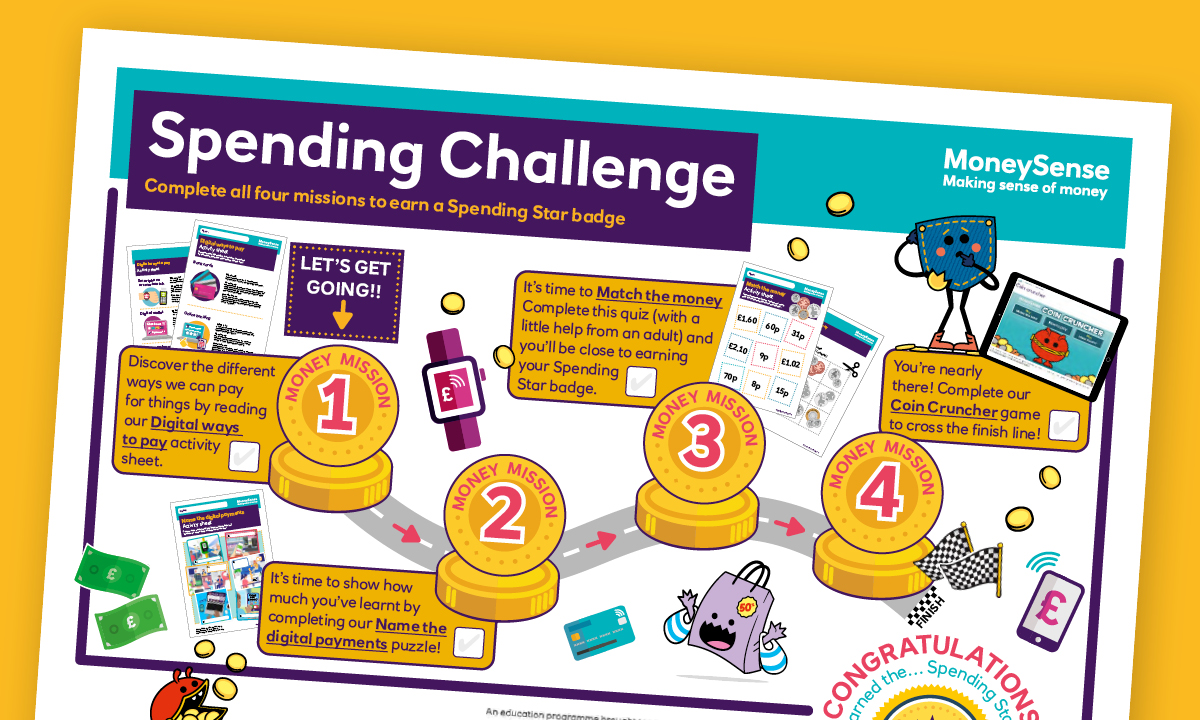

Related activities

Want your child to find out more for themselves? Here are some activities to share with them.

Activities:

Activities:

Poster:

Poster: